A History of Braces

While braces could easily belong to a bygone era, these accoutrements have moved past their purely practical purpose to become a fixture among the sartorially inclined.

The etiquette of black tie insists that you wear them. And most tailors speak in their favour for the better line they afford your trousers – indeed, the Prince of Wales and future Edward VIII once fell out with his tailor when he insisted on wearing his strides with belt loops instead.

Braces, for sure, are a curious contraption. More apparatus than accessory, they're the kind of thing befitting a patent, of the kind one Samuel Clemens – better known as Mark Twain – filed in 1871. Or as, in 1894, David Roth did for the first metal clip-on braces, the more practical but decidedly less elegant alternative to the button-in style, much as elastic, in style terms, doesn’t quite compete with the more traditional woollen box cloth or the silk pair in a regimental stripe from the likes of Sera Fine Silk.

Yet, despite being steampunk-esque, braces are something men often quietly become attached to – literally and figuratively – such that they can barely do without the sense of security that being strapped into a pair brings. When war with Germany was declared in 1939, the first thing actor Ralph Richardson is said to have done is dash to his tailors to buy six pairs of Albert Thurston braces, lest rationing make their later acquisition impossible.

He chose well: Thurston was established in 1820 as one of the earliest specialist makers of braces, helping to make the Y-shaped back – which replaced the X-back, which in turn superseded the H-back – the standard. It also introduced such contrivances as the Double Albert Extender and, more intriguingly, something referred to as the Chest Improvement Accessory – or CIA for short, and for its similarity to a shoulder holster. Said CIA was devised to force the shoulders back and improve one’s posture, something even more everyday braces tend to do.

It was etiquette, in fact, that was said to be the undoing of braces as the everyday choice: considered to be, in effect, an undergarment, and so not suitable for any gentleman to display – they were typically hidden under a waistcoat well into the 20th century – it was the heatwave of 1893 that first saw men, in droves, make a switch to the belt. The belt, of course – multi-functional, easily adjusted, easily made – had already been worn in some form for millennia.

Yet while braces seem both to be outclassed by the simplicity of a strip of leather around the waist, and to belong to a bygone era of redundant accoutrements that also includes the likes of sock suspenders, spatz and detachable collars, they continue to hold their place in the male wardrobe, and at both ends of the sartorial spectrum.

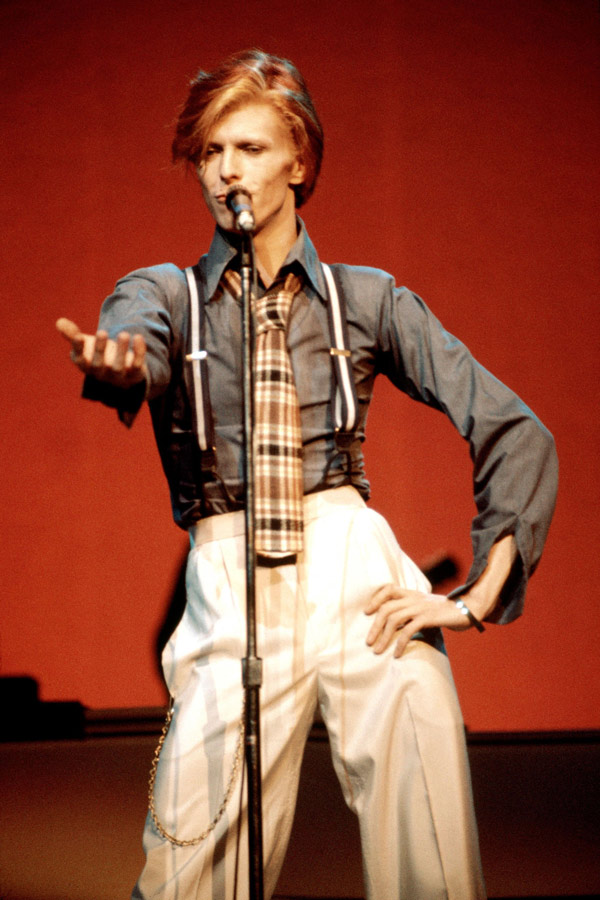

On the one hand they’re synonymous with 1980s power dressing – the Gordon Gekko effect, with Wall Street actually inspiring a rash of copy-cat dressing in financial quarters around the world, such were our heroes then; or the dandy inflection of David Bowie’s German Expressionist Thin White Duke phase. On the other, they chime with the erstwhile working classes, with braces resonating alike with the practical style of Little House on the Prairie or Chas ‘n’ Dave, the thuggish Droogs of A Clockwork Orange and the misperceived thuggishness of skinheads.

“I want all you skinheads to get up on your feet, put your braces together and your boots on your feet and give me some of that old moonstomping,” as Skinhead Moonstomp has it. For the immaculately turned out first wave of skins, brightly-coloured, one inch-wide elasticated braces – clipped to cropped jeans – were more a show of working class credentials than indicative of the need to keep up their tight-fitting orange tab Levi’s.

Yet none, perhaps, is an entirely positive image for braces today. Perhaps we need to keep in mind their origins: what is believed to be the original French invention, ‘bretelles’, with strips of silk ribbon affixed to one’s trousers by way of buttons, favoured by Napoleon and, once the idea had spread north, embraced by Beau Brummell. In fact, those who wear braces unabashed tend to be those who wear them most successfully. Look on in admiration. They will appreciate your support.