Jaquet Droz: Enamel Instincts

At the turn of the 19th century, Switzerland’s most pioneering watchmakers were making history not in the picturesque Jura Mountains towns of Geneva and Neuchâtel, but farther afield — in the uncharted, lands of China. Bovet, Piguet & Meylan, and Vacheron Constantin, among them, were seduced by the land-of-a-billion, both professionally and personally: for example, after a 12-year stint in Canton, Édouard Bovet returned home in 1830 flush with cash, success and a four-year-old, half-Chinese son.

Yet few can lay claim to having had the ear of the Chinese emperor himself — quite literally. That honour goes to Jaquet Droz, whose genius, musical automatons and mechanical timepieces so enthralled the Qianlong emperor in the 1770s that the ruler set up his own national office to import and trade in such wondrous objects. In 10 years, Jaquet Droz exported more than 600 pieces to the most discerning of Chinese patrons, the creations of which combined highly complicated movements with the bling of their day: extravagant enamel work, pearls and precious stones. The stunning mechanical marvels set the tone for Jaquet Droz’s serious approach to craft, which courses through its D.N.A. today.

Founder Pierre Jaquet Droz was destined to sell to kings. His early long-base clocks, dreamed up in his La Chaux-de-Fonds workshop that he set up in 1738, defied those of his time. By 1773, Pierre and son Henri-Louis were wowing royal courts throughout Europe with their remarkable humanoid automata — essentially life-size, hand-wound androids. The robots could write, draw and sing, some fully clad in ruffled shirts and satin breeches — plus with painted toes and fingers, bizarrely. Whimsical and truly astonishing, they were also sinister to some; in Madrid, the Inquisition condemned Pierre to death for allegedly practising black magic, and he was saved only by the Bishop of Toledo.

All this made for fantastic branding, enabling Jaquet Droz to go on and sell its timepieces, some of which are highly coveted today. At Sotheby’s last year, for example, a collector paid $2.5m for a 1786-87 gem-set, singing-bird automaton scent flask. Standing 16cm tall, the work featured a white enamel dial and diamond-set balance on one side, an articulated ivory bird on the other. Pumping out song via a six-valve pinned cylinder, it “predates what one normally sees, which is whistle and piston”, says Daryn Schnipper, chairman of Sotheby’s international watch division. “This has a tiny organ called a serinette. The miniaturisation factor is insane.” So too is the decoration. Translucent pink enamel, bezels and alternating rubies and pearls surrounded the bird, all further ensconced by Renaissance-style gold paillon arabesques over a rich-blue background. The piece is pretty over the top — and out of reach — for most, but such automata are synonymous with Jaquet Droz today, even if some of its most well-known modern timepieces are starkly pared down in comparison. “They are recalling their history,” says Schnipper.

Cue its Grande Seconde iconic collection (‘iconic’ here being loosely used, as it launched only in 2002, two years after Swatch Group stepped in). The design takes after an 18th-century pocket-watch and is notably minimalist save for a figure-eight leitmotif fashioned from an overlapping hour-and-minute display at 12 o’clock, and a seconds counter at six.

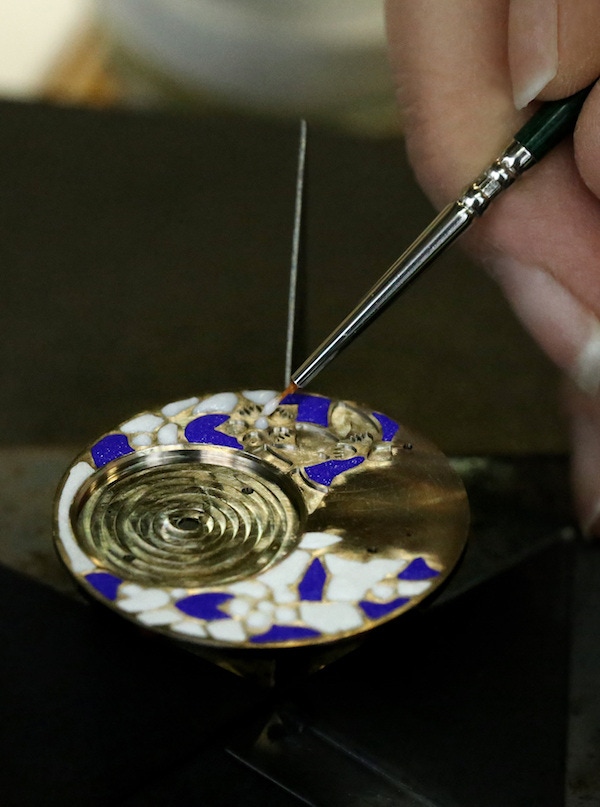

But underlying it is the art of grand feu enamelling. An ancient craft that first mixes glass powder with oxides, the formula is then finely painted onto a solid gold dial, before ‘great firing’ the whole lot at a searing 800-850°. Multiple bakings are required, often at varying temperatures and times that would test the patience and skill of any Michelin-starred chef. And it can all fall apart at the last minute. Breakage is common, and a speck of dust at the end can release a bubble, botching the entire endeavour.

Grand feu enamel has recently been cropping up on the dials of many brands, most notably in all their polytechnic, glossy glory. But one flush in monochrome, uniform white — as found in Jaquet Droz’s ‘ivory’ dials — has a splendid, back-to-basics appeal. Such a deep and lustrous pale is deceptively difficult to achieve in the minefield of grand feu. Simplicity, to quote Da Vinci, is the ultimate sophistication.

In 2016, a dual-time model was introduced, involving a new self-winding movement that powers local time on the upper display while the lower doubles as the traditional seconds dial and 24-hour second time zone. A further date complication was added, indicated by a red-tipped hand. Other features on the 18ct red-gold piece remain true: 43mm, 65-hour power reserve, off-centre displays, and contrasting Roman and Arabic numerals. It’s the globetrotting version of the Grande Seconde that pays direct homage to Pierre Jaquet Droz — the man supposedly kept La Chaux-de-Fonds time on his watch while jaunting around the globe.

The asymmetrical version in grand feu ivory is also worth mentioning. It’s a cool subversive take on this ‘instant classic’, all the while remaining discreet. Jaquet Droz, after all, is for the man who, with his safe full of Pateks, Cartiers and Rolexes, seeks something unusual — whether it is some crazy bird chirping away in a miniature flask or an unexpected enamel watch dial that evokes the infinity symbol. It exudes an in-the-know aura. As one retailer told me: “You can wear a Grande Seconde in the boardroom and most people wouldn’t know how much it cost — or how much you’re worth.”

The ivory enamel dial also makes a cameo in the Petite Heure Minute Monkey, Jaquet Droz’s annual homage to the Chinese calendar — this time paying respects to the legendary Sun Wukong, or Monkey King. Though it’s not like respects are really in order: the dial depicts the Garden of Celestial Peaches, of which Sun Wukong was charged with protecting, only to see him polish off all the sacred fruit. Nevertheless, the playful 18ct red-gold watch, limited to 28 pieces and available in either 35mm or 39mm, is a masterclass in miniature painting, while further highlighting the brand’s bespoke service. Customers can order any motif they desire, from personal zodiac signs to, say, a beloved yacht, and all masterfully executed with the same exacting detail.

At the other end of the spectrum is the artisanal wonder that is the house’s paillonné dial. The 18th-century paillonné technique refers to tiny, gold-leaf cut motifs that are individually applied to a dial. But this is, in Jaquet Droz’s case, after the dial has been first engraved with a sun-ray motif then painted with semi-transparent enamel. Only after the requisite firings are the gold paillons hand-set, followed by more enamel. A translucent enamel fondant tops it all off, which, working its final grand feu magic, brings a profound depth to the piece. Final polishing adds the last layer of lustre.

Where past designs were more floral, new to the range is a masculine, tapestry-style theme, and in new colours: grey, blue, violet and red. The self-winding tourbillon, limited to eight pieces, is also new, but my choice would be the classic in blue, not least because it best shows off a rich hue that, in the world of grand feu enamelling, has among the highest rejection rates for success. It’s also the most magnificent, and would do any confident and cultivated man justice. An art-world player or even a classical music conductor, perhaps, who might pair the resplendent piece with a midnight-blue dinner jacket. Or even glorious jacquard. Go on, the kings would approve.